The Osamu Tezuka Story

Toshio Ban and Tezuka

Productions

translated by Frederik L.

Schodt

Stone Bridge Press, 2016

The Osamu Tezuka Story is,

like Tezuka's body of work, a gigantic, awe-inspiring thing that both

stuns and entertains. Part corporate/pop cultural history, part

struggle of the artist as a young, middle-aged, and older manga-ka,

the book delivers four decades of the manga publishing world and the

life of its most popular creator, whose work impacted Japan and the

world. As a bonus this book and its 900 pages also deliver a great

upper body workout. Because... it's big.

Anyone interested in

Japanese comics or animation knows Tezuka's name. Convenient Western

shorthand casts him as Japan's Walt Disney, a protean creator of

world-renowned characters who dragged an artform into a licenseable,

immensely profitable future; but he combined Disney's innate grasp of

public taste with an inhuman work ethic and a fiercely competitive

drive to excel. English-language material about manga's early days is

rare, apart from Ryan Holmberg's deep-dive work at TCJ, and Western

fans rely on getting bits and pieces of history sideways through old

fanzine articles and questionable anime blogs informed by

half-remembered nerd conversations. Discussions about Tezuka usually

involve some self-appointed expert claiming Tezuka invented manga (he

did not), or Tezuka invented anime (he did not) or that Astro Boy was

the first animated TV show in Japan (it was not) or that the first

shoujo manga was Tezuka's Princess Knight (nope). Hopefully this book

will nip future tall-tale-tellers in the bud, because the truth

behind Osamu Tezuka's genius is vastly more interesting than any

fakey list of 'firsts.'

|

| color Astro Boy/Tetsuwan Atomu splash page from Sept. 1965 Shonen |

Readers already familiar

with Tezuka's exports like Astro Boy, Kimba The White Lion, Black Jack, Adolf, and Phoenix will enjoy seeing the creative struggles

behind their favorites, and if they weren't already aware of the

punishing demands of a professional manga artist, Tezuka's tireless

pace and unstoppable mania for creation will dumbfound. The Osamu

Tezuka Story details how habits of hard work were fostered early in

Tezuka's life. The Osaka-born Tezuka found inspiration in the

discipline of long distance running, a lifelong passion for music,

movies, and insect collecting, and a love of cartooning encouraged by

the adults in his life. The demands of Japan's wartime culture would,

in Tezuka, result in an amazing ability to focus on tasks and

maximize his own effectiveness, to juggle several different

challenges at the same time, and to deliver results in widely

disparate fields – talents that would serve him well in surviving the

rigors of the immediate postwar period, breaking into the

children's manga field and, at the same time, interning as a

medical doctor. Try it sometime, kids.

|

| #oneperfectshot | Night Call Nurses | 1972 | dir. Jonathan Kaplan | prod. Roger Corman |

Choosing comics, Tezuka

found himself in the center of a postwar children's magazine boom.

Tezuka's Shin Takarajima, or "New Treasure Island", created

with Shichima Sakai, would be a breakout hit for Tezuka. The 50s

manga explosion produced an entire generation of young manga artists,

battling their punishing schedules and occasionally relieving stress

with three-day blowouts. Future manga stars like Shotaro Ishinomori,

Fujiko-Fujio, Fujio Akatsuka, and Leiji Matsumoto appear in Tezuka's

orbit as young hopefuls. Did Tezuka give his young manga acolytes

aphrodisiacs to fuel their late-night manga sessions? Read the book

and find out!

A popular talent feeding the

pop culture needs of millions of Japanese children, Tezuka would find

himself working on eight stories for eight different publishers

simultaneously. Editors would haunt Tezuka's foyer fighting for

priority, sometimes confining him to a hotel or, failing that, forced

to track him down from place to place to beg for pages. Tezuka's

organizational skills allowed him to direct production teams, with

Tezuka outworking even his most dedicated assistants, and he

developed a complex system to indicate to assistants the kinds of

crosshatching, shading, backgrounds or environmental effects for each

panel. He could direct the composition of manga pages from another

room or, as communications technology improved, from another city

entirely.

The late 1950s appearance of

more adult "gekiga" manga challenged the competitive Tezuka

to create works with more adult themes and a more realistic art

style. At the same time he was working with Toei Animation on the

feature length Son Goku film Saiyuki ("Journey To The West",

known in America as "Alakazam The Great"). Soon Tezuka was

pouring his manga profits into his other love, animation.

By 1960 Tezuka had developed

a production system for working with assistants and editors, had

completed his doctoral thesis, had written a live-action TV show, and

was embarking on his own animation production, with facilities

purpose-built into his new home. Showa-era anime buffs will be

interested in the production details of Astro Boy and early shorts

like "Drop" and "Pictures At An Exhibition", and

fascinated by Tezuka's cost-cutting animation choices, choices that

are still felt today. Tezuka's obsessive filmgoing paid dividends as

he utilized cinematic techniques like montage and cross-cutting to

inexpensively and quickly emphasize drama. His already overstuffed

work schedule became even more hectic; story conferences would be

informal, Stan Lee-style verbal exchanges where Tezuka would describe

the plot and the main visuals, leaving the layout & genga for

staff artists to complete. This would expand to a shift system that

worked around the clock. His corporate structure split and split

again, with one company handling his TV animation, one company

handling his licencing, and one for his manga publishing.

|

| early 1960s hardback "White Pilot" |

Tezuka's kingdom would, like

the rest of us, be battered by the shocks of the 70s. The decade

would see his animation studio go bankrupt and Tezuka struggle for

creative relevance in the face of personal and professional crisis,

leading him to innovate new manga for children and adults and make

global connections that will take him to China, Europe, and Los

Angeles' nascent Cartoon/Fantasy Organization. Tezuka's animation

would rebound, inaugurating a series of yearly TV specials for NHK

and production on experimental, artistic works. Sequestering himself

in a private studio, the decade saw Tezuka working harder than ever,

inspired by deadlines and pressure yet never abandoning his

painstaking attention to detail. Anime fans will appreciate the

research and technical challenges he and animator Junji Kobayashi

faced in creating the opening scene from his film Phoenix 2772, a

dramatic "one-take" shot of differing camera angles and

perspectives that took two full months. Kobayashi would later be

instrumental in creating Tezuka's award-winning 1984 masterpiece,

"Jumping."

|

| Phoenix 2772's transforming robot love interest, Olga |

Throughout the 1980s Tezuka

continued his Phoenix manga, pushed ahead with new manga like Adolph,

Neo-Faust, and Ludwig B, visited France and Brazil, produced a new

color Astro Boy TV series, achieved animation awards and manga

awards, and continued his all-nighters and his deadline struggles up

to and through his increasing health problems. Osamu Tezuka would

pass away in 1989 at the age of 60, an age that these days seems far

too young. However, in those sixty years he filled every day to the

fullest, leaving a life's work unmatched in any field, a life's work

the 900 pages of The Osamu Tezuka Story can only begin to describe.

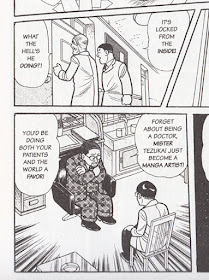

Toshio Ban's artwork is

friendly, clean, photo-referenced to the hilt (some of the original

photos can be seen in Helen McCarthy's excellent The Art Of Osamu Tezuka), and close to Tezuka's own style but not so close that the

bits of Tezuka's own work seen occasionally don't stand out as wildly

individualistic. The Osamu Tezuka Story proves Tezuka's own thesis

of the universality of cartooning as a visual language, reminding us

all of the vast market for educational, vocational, historical, and

otherwise informational comics, a market that Japan has embraced

wholeheartedly while the rest of the world makes do with Ikea

assembly guides and comics about military courtesy or Dagwood's

mental health problems.

Frederik Schodt's adaptation

grapples with entire lifetimes and cultures, world wars, Japanese

educational and medical institutions, the ins and outs of the manga

industry, right down to specific animation techniques and obscure

Japanese insects, yet never fails to keep the material relevant,

interesting, and accessible to the general reader. Schodt served as

Tezuka's translator on some of his American visits, giving us the

unique situation where a translator is translating scenes of himself

translating. Time really is a flat circle, I guess.

Every once in awhile the

book feels the need to emphasize Tezuka's genius by describing his

otherworldly excellence in fields unrelated to manga; astounding

onlookers by mastering "extremely difficult scores" without

any formal piano training, memorizing phone numbers, dictating

telegrams, comprehending highly specialized texts, and caricaturing

classmates from memory. Listing these prosaic "achievements"

only adds a hagiographic tone to the text, and anyway, they're

completely overshadowed by the tremendous achievements Tezuka

actually did achieve in his actual recorded career.

Published as it is by Tezuka

Productions, The Osamu Tezuka Story has a definite focus on the

positive. The bankruptcies of Mushi Productions and Mushi Pro Shoji

in the 1970s are mentioned but explanations are vague; the copyright

disputes that kept Astro Boy out of the public eye for years are only

touched on briefly, and some misfires - like the 1950s live action

Astro Boy TV series that Tezuka later briefly pretended didn't exist

- are not mentioned at all. And while some readers may at times want

a franker, more candid account of Tezuka's life, let's face it, that

isn't what corporate biographies are about; "Tokiwaso Babylon"

this ain't.

What The Osamu Tezuka Story

is, is a comprehensive look at the life of someone who always worked

harder, who always thought he could do better, who was surrounded by

amazing talent and used that rivalry to spur himself to greater

efforts. It's the life of a man who survived war and occupation and

disease and who lived to create, every minute of every day. A man

who built studios and empires and tore them down and built them up

again, because he never stopped creating. A man who could tell you

the names of the stars in the sky and the names of the bugs in the

dirt, and then stay up for three days drawing comics, because that

was what he was, a creator.

28 years after his passing,

his work remains popular and influential as reissues, remakes, and

new visions bring his characters back to life. Western audiences have

enjoyed their own Tezuka boom with his manga appearing here in ever

increasing numbers. And with The Osamu Tezuka Story in English, we

can more fully understand every part of Tezuka's boundless genius.

-Dave Merrill

Wow, this is really an enlighten to me, I also agree Astroboy is just the first popular anime series ever.

ReplyDelete