Author's note: This article was originally published in the twelfth (Spring 1999) issue of the fanzine "Let's Anime," and was intended to be titled "X: Mild Gift", though this title somehow got deleted. It was written as one unbroken sentence, and is reproduced here as before, minus the transcription errors born from trying to read my handwriting.

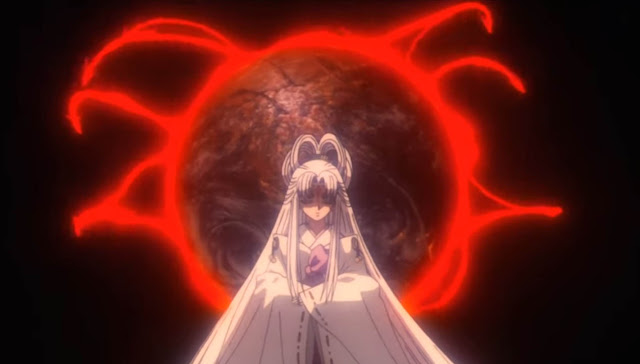

Traditionally, the letter "X" has been used, amongst other things, to denote the location of buried treasure, but if there is any treasure to be had hereabouts, it has apparently been safely sequestered beneath so many strata that it could casually rub hips with Australopithecus, many of whose slump-backed and shambling contemporaries could have doubtlessly penned -- would that there had been pens available -- a less inchoate smattering of surface detail and subsurface void than this gucky goofwad of angst and somnolence from the much-vaunted, all femme banal studio CLAMP, for oozing languidly in and about the flickering frames of this latest stack of overhyped Japsquiggles is an all-too familiar premise handled all too ineptly: that of more super-psychics rending more abstract art out of more Tokyo in accordance with that least empathetic of all motives -- DESTINY, with a capital everything -- thereby bequeathing us with a film wherein opposing spoon-benders extraordinaire regularly meet and throw down in the inner city like astral-traveller Crips defending their turf for no reason even they could provide after slipping around some universal corner in the form of a big computer animated Espo-Barrier to ensure that nothing untoward resulting from their clandestine tête-à-tête should bring undue mental or physical stress to any passing salaryman or other perpetually unseen denizen of the soon-to-be slowly melting and crumbling down skyscraper arena once all hell - no wait; that sounds too exciting - all heck breaks loose within this rendition of the long venerated monster magnet Tokyo, a Tokyo which would seem - would that such a thing were possible - to be even emptier than the ground-floor characterizations of our disgruntled ex-Psychic Hotline goon squads, whose members snuff their porchlights like Black Flag-shooting junkie fireflies in a microwave mere minutes after their passing introductions, leaving these unidentified saboteurs (from space) to remain unidentified, unwept and unsung even as the cycle begins anew, a trend which inevitably and most unfortunately bleeds copiously over into what most closely approximates a central theme here and is ultimately manifested in this two-hour Nyquil substitute's most egregious failing: the film's utter inability to handle with any amount of honesty the very real-world tragedy of the dissolution of friendship, a thematic concept it would seem to have borrowed from the far more deftly executed Akira and subsequently stripped of all its considerable impact by once again forsaking deliberate choice and personal motivation as reasons for conflict in favor of advocating a hackneyed "devil-made-me-do-it" stance of predestination that manipulative charlatans the likes of Nostradamus, Jean Dixon, and countless other two-bit fakers in between have used to bilk and delude the credulous layman throughout the ages, a shortcut cheat that robs the viewer of any possible emotional connection with these characters via either a personal recognition of the pain inherent in a breach of trust, or identification with the fate of one who has chosen their steps a tad too recklessly and must lie in the bed they've burned with their own two hands, each of which presumably held a match or other incendiary device in this hypothetical metaphor that serves to illustrate, albeit in an unnecessarily aggrandized way that has doubtlessly begun to become at least mildly obnoxious to many readers who may tire of unending and, for the most part, mindless digressions like this one, the undeniable fact that while some personal style, mostly apparent in the big, dreamy, mascara-encrusted eyes of our pretty-boy cast members, may still show through and betray the film's origins, by no means is an all-female animation studio any more intrinsically interesting or creative than an all or at least predominantly male animation studio due to the simple fact that the wellspring of their success was a common one, a shared history of stories, style, and executions whose overuse in innumerable examples of the Japanese animation industry's progeny has created a vast landscape of homogeneity in which various constituent ingredients are mixed seemingly at random and squirted forth by the corporate machine for public consumption like elementary school lunches, the ingestion of which merely provides temporary satiation and no real nutritional value for anyone save the over-hungry wallets of a breed of providers whose past innovations have become today's codified laws, whose once adventuresome spirit now staggers, choked and wheezing, down a well-travelled path like a pioneer who has stumbled across one boa constrictor too many and no longer dares to take chances on new avenues of exploration, until a form of creative expression that once shone like the sun wore out its welcome with random precision and sits stripped of its luster as content winds its spinless coils and slithers out of sight, to be replaced by prefab plastic gloss whose cross-format focused and scientifically harmonious sheen nevertheless manages somehow to remain dull and lifeless as it is gradually lacquered over a once superlative accomplishment like a film of dirt, slime and verdigris slowly encrusting a long-since touched fire extinguisher that hangs within the cobweb-ridden hallway of a rickety, unkempt hotel on the lame side of Tepidtown and waits with fingernail-chomping impatience for gallons of rubbing alcohol to flow through the strip and burn it clean, spiralling downwards ever further into oblivion as the city fathers watch with little interest, cold and implacable like a rock, like a planet, like a fucking atom bomb, counting their ill-gotten and undeserved gain as decay slowly encroaches upon and erodes the foundations from beneath the toxin-spewing industrial infrastructure out of which their atrophied livelihood was once begotten, until comes the fated hour that their sleep is broken by the somehow unanticipated news that the city is burning that night and they are left to wonder, with some measure of chagrin, if there might possibly be a handy fire extinguisher about someplace now that they might appear to be consigned to immolation in the beds they had always thought were kept well clear of both fire and flame-producing agents as their own dearth of maintenance washes the whole dumb town into the bowels of the earth with a final climactic "slurp" that goes forever unmourned, much like those people in that stupid X movie, which, as you may have forgotten, is the alleged subject of this overwrought diatribe, and the suddenly recurrent mention of which serves as a convenient stepping-stone from whence to dive face-first into the final salient point remaining to be discussed within the helter-skelter syntax of this bastard collection of adjectives and similes: my utter and unending confusion as to why there exists any such thing as a new anime fan, for whether you take that to mean one who has newly become a fan of anime, or one who is a fan of new anime, the puzzle remains an insoluble one in that it requires some understanding of how, when a film like X is a pretty average example of storytelling quality, superior animation or no, anyone can sustain interest in the medium long enough to become so singularly a fan of Japanese animation instead of cinema in general beyond a passing, or at least what would be passing in a brighter, saner world, sense of novelty stemming from the obvious differences from American animation it clearly possesses, a novelty which, though notable, is hardly sufficient to rescue this film from empty genericism, as were the efforts of exceptional animation director Rin Taro, who, like his comrade-in-charms Mamoru Oshii with Ghost in the Shell, simply was given nothing of meaning or value around which to weave his often beautiful images, an unrealized strike in the positive column that most anime is bereft of from the very get-go, encumbered as it so often is by a collection of demerits weightier than James Cameron's Titanic budget, or for that matter, his Titanic ego, leaving the true film lover out in the cold with his nose pressed against the glass and his tongue stuck to a lamppost because he was an idiot to mourn the paucity of artistic achievement remaining since the passing of the Good Old Days, a time which, though hardly devoid of crap, nevertheless boasted a more varied range of quality, so that amongst the myriad ranks of product packed sardine-like in those J-trains downtown would be the occasional good film or series that actually stood a decent chance of rubbing hips with another good or at least decent idea instead of some swill-penning cave bum with bad posture, a regrettably lapsed state of affairs for an artform that once invited and bore close scrutiny for good reason and now continues to plow forward as a mere result of its own inertia instead of true content, a fact somehow lost on the masses of trendseeking New Anime Fans who grope for whatever quick-fix, flash and dazzle ephemera they can most easily reach and crown Best Show Ever until it too deteriorates and quickly fades away so that its place may be subsequently filled with yet more of the same exact same, and who may indeed honestly continue to be entertained by films of this type and style, but whose enthusiasm no longer parallels mine, which once gripped me with such fervor back in Year One but has long since passed out on the couch due to one - or one thousand, for that matter - too many examples of all style and no substance born out of a medium that once showed true promise, which is why, in not so many words, I think that this film sucks horse butts.

-review by Matt Murray

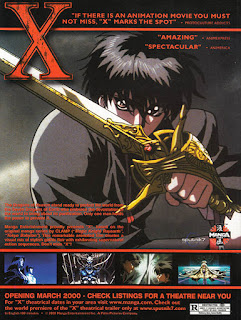

X/1999, a Madhouse film based on the 1992 manga by CLAMP, was directed by Rintaro and distributed by Toei, with production assistance from Kadokawa Shoten, Victor Company Of Japan, MOVIC, Sega, and Bandai Visual. The film was released in Japanese theaters in 1996 and on DVD in the US in 2000.