So recently we went out on a snowy November night through accident-choked streets to Toronto’s Hudson's Bay Center, where the Japan Foundation was hosting a screening of the 1983 film Genma Taisen / Harmagedon. We promptly got lost in the men’s department of the Bay, got ourselves turned around, onto the elevator, and into the Japan Foundation's screening room, just as the film opened with shards of destroyed planet sailing past the Moon.

By the time most Western anime fans were able to see 1983’s Genma Taisen, or Harmagedon as the English language text would have us call it, they'd already ingested most of the anime Harmagedon would inspire. They'd seen Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira and similiarly apocalyptic Rintaro works like X. They'd probably even watched Project A-Ko use KFC pitchman Colonel Sanders to spoof Harmagedon without knowing what Harmagedon was. They'd seen a thousand psychic teenagers glowing red or green or blue or yellow, battling ultimate evils with flashing mental beams. Harmagedon was old news, stodgy, unfashionable, not nearly edgy or bloody or violent enough for anime fans circa 2003.

And you know what, if you take Harmagedon out of the context of 1983, they just might have a point. It's a long, indulgent, prog-rock concept album of a film that makes you feel every minute of its two-hour-plus running time, the latest in an interminable odyssey of Japanese animated science-fiction epics that meandered their way through Youths in Arcadia and strolled past the Legends Of The Super Galaxy (130 minutes each), wandered over Towards The Terra (a relatively terse two hours), and poked their way through all one hundred and forty-five spine-destroying minutes of the aptly-titled Be Forever Yamato. What I'm trying to say is that anime films in the early 1980s were long, baby, and if your attention span has been destroyed by three-second Adult Swim interstitial bumpers, you’re going to find the early 1980s anime film aesthetic paralyzingly dull.

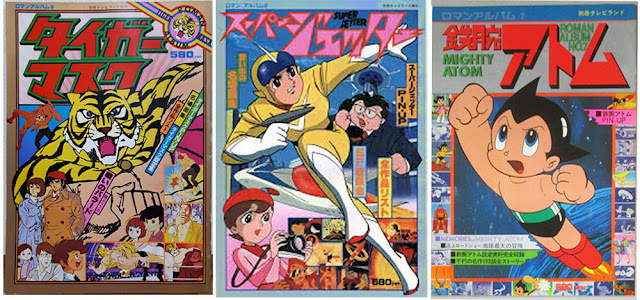

But slide Harmagedon back in that 1983 context. Put it up against the space robots, the Matsumoto blondes, and everything else that was happening in the contemporaneous anime world, and you've got something special, a New Age epic fantasy of Earth’s psychic warriors recruited by the universal love consciousness to do battle with the forces of chaos and evil that infect the outermost galaxy and our innermost selves.

|

| a few of Harmagedon's Psionics Fighters |

This film is director Rintaro's cinematic coming out party, filled with terrific bursts of color swooping and bubbling and popping out of the darkness whenever psychic powers are emanating or lava is bursting or flames are leaping. Parts of Harmagedon are perfect pieces of film-making - where alien cyborg Bega and psychic princess Luna try to scare-start Joe's ESP by freezing Shinjuku and smashing a construction site, where the intangible, roller-skating Sonny and his gang loot a ruined New York and are machine-gunned by the NYPD, where every authority figure is possessed by monsters from beyond space, including amiable, elderly doctors, and the smiling old man just stands there amidst the molten rock of an erupting Mt. Fuji to tell us he's in charge of destroying the Earth.

|

| three faces of Genma |

Harmagedon was Katsuhiro Otomo’s anime debut, smashing the audience with his aggressively realistic characters, all frantically struggling to survive the disintegrating urban cityscapes they’d been dropped into, Tokyo and NYC ruined and chaotic, the familiar landmarks drowned in dust or the East River. It’s a film that feels like a trial run for Akira, because it is, and anime hadn’t seen anything like it, certainly nothing like the cyborg survivor Bega. A symphony of excellence in mechanical design, Bega is all rounded shapes and interlocking parts, his armor shifting and molding itself into new shapes to counter every threat, a mecha aesthetic so far removed from the typical super robot/real robot anime tropes that it might as well actually be from another planet.

All this is on top of art direction by the five-time Anime Grand Prix award winner Takamura Mukuo. If you watched Galaxy Express or Adieu 999 or his later Dagger Of Kamui or that Devilman OVA or, say, Stop! Hibari-kun, or any number of other anime productions, you'll recognize his stunning background work; his sweeping landscapes, his operatic, lushly lit clouds, his gigantic architectural structures looming against ominous skies, all crimson and azure and emerald and oily grey browns, a perfect accompaniment to the Madhouse animation. Madhouse is, of course, Madhouse, delivering stunning scenes of big-screen animation that no one in Japan or anywhere else on Earth was doing that year.

|

| Harmagedon's post-Genma Tokyo |

Adding the international cherry on top of this confection of talent is legendary prog rock keyboardist Keith Emerson, whose work with The Nice and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer had moved the synthesizer from a electronic gimmick to a stadium-pleasing weapon of mass rock entertainment, and whose score for Harmagedon capably moves from profound to whimsical, with the occasional visit from Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.

Without flamboyant producer/publishing empire heir Haruki Kadokawa and his aggressive film production schedule, Harmagedon might never have been made. Kadokawa had flipped a stodgy publishing house into a pop-fiction juggernaut, turning his mass appeal fiction into crowd pleasing cinema blockbusters. Harmagedon was Kadokawa’s first animated film, to be followed by Dagger Of Kamui, the sadly neglected Time Stranger, Manie Manie/Neo Tokyo, Five Star Stories, and Silent Mobieus before Haruki found himself doing a stretch in Shizoka Prison on a cocaine smuggling conviction. It’s a helluva drug, kids. As a paperback bestseller turned motion picture extravaganza, Kadokawa’s Harmagedon resembles the bloated, baroque, literary-pretentious middlebrow epics Hollywood spent decades shoving into America’s long-suffering eyeballs; even when these movies succeed, they remain emblematic of an era of lavish excess. When we say anime is "a medium not a genre," this is what we're talking about, that Japanese animation can give us both cheap exploitative genre trash and crowd-pleasing mainstream spectacle.

|

| we heard you liked Hamagedon so we advertised Harmagedon during Harmagedon |

If you’ve seen a Japanese cartoon in the past thirty years you know what Harmagedon’s about: a Japanese teen's awakening ESP power drafts him into the front lines of the Ultimate Battle Between Good And Evil. Our mopey hero Joe Azuma won’t try out for the baseball team, is dumped by his girlfriend, and generally has a case of the teen angst. Then he meets Luna and Bega and he’s suddenly having visions of cosmic love entities millions of light years distant, manifesting his latent psychic powers against the forces of Genma, seen here as shape-changing devils that can take the place of your classmates or your friends or your local beat cop. Joined by an international crew of psionic warriors, Joe struggles through a world demolished by cataclysms and overturned by chaos, towards the final psychic showdown with Genma.

Harmagedon had a long road to the screen: the original early 60s manga ran in Weekly Shonen Sunday with a script by former 8 Man author Kasumasu Hirai and art by future Kamen Rider creator and record-breaking manga-ka Shotaro Ishinomori. Hirai, one of Japan’s SF giants, would go on to author the “Wolf Guy” series (itself the basis for a Sonny Chiba film), the Japanese Spider-Man manga, and a slew of other fantastical works. He’d adapt the ‘67 Genma Taisen manga into a series of Genma Taisen novels that would continue for decades in 2008, and he’d write the Ishinomori-drawn Genma Wars Rebirth manga for Tokuma Shoten's Monthly Comic Ryu for five years beginning in 1979. This would become the basis for that ‘02 Genma Taisen anime series that people don’t talk about much.

|

| Harmagedon, 1960s style. Trigger warning: cartoon stereotypes |

After destroying his hand writing all those Genma Taisen novels in longhand, Hirai was an early adopter of the word processor. He was also an early and influential member of Shinji Takahashi's God Light Association, a syncretic, New Age precursor to today's Happy Science. The more overtly religious overtones of Harmagedon begin to make sense when you learn the author probably believed wholeheartedly in a universal super-consciousness striving to enlighten all sentient beings to their innate spiritual and psychical nature.

Ultimately, in spite of its all-star creative talent, its thirsty-for-international-blockbusters producer, and its occasional bursts of cinematic energy, Harmagedon spends a lot of time spinning its new-agey wheels. The film has the pieces and the pedigree to be great, but all the ingredients never quite come together. In between Harmagedon’s discrete moments of visual excitement, there's a lot of quiet filler, the film moving in little funhouse-ride bumps from one scene of blank-faced characters silently staring at each other, to another scene where blank-faced characters silently stare at each other. Himself a jazz musician, Rin Taro knows it's what's in between the notes that counts, but in Harmagedon he is still finding his tempo.

|

| we all knew the NYC real estate bubble would pop eventually |

Speaking of music, with Harmagedon's soundtrack Keith Emerson is never allowed to deliver the kind of prodigious electronic synthesizer freakout he’s famous for - and if you aren’t going to let him go nuts, why hire him? Go on, look up footage of Keith playing keyboards while suspended upside down forty feet in the air before an audience of twenty thousand cheering fans. You don’t hire that guy to *not* freak out.

The cast of characters is a Cyborg 009-style parade of tokens and stereotypes, from the Indian mystic to the big Native American, from the Middle Eastern Turban Guy to the Chinese girl who practices kung-fu in her little Chinese outfit. The American Sonny made the jump from what was even for 1967 Japan a dated and offensive black-kid stereotype to a very 1980s African-American NYC teen, decked out with baseball cap, track suit, sunglasses, roller skates, and Walkman. Harmagedon’s Sonny is a welcome flash of style, but the audience goodwill vanishes immediately at the sight of his white-flight stereotype gang, a racist suburbanite’s nightmare fantasy of ignorant, heavily armed black looters. It’s a shame, too, because that scene is one of the best-directed of the film, a Sergio Leone ambush in the deserted streets of Fifth Avenue.

Harmagedon attempts to address racism head-on when Luna’s prejudice-induced failure to psychically connect with Sonny is called out by Bega. “Is it because he’s black?” he rebukes. That’s right; her racism is so obvious that even 4,000 year old cyborgs from other galaxies can pick up on it. Luna, herself a Transylvanian princess (?) isn’t given a whole lot to do other than to bounce exposition off Bega and, in the fashion of Ishinomori’s Cyborg 003, act as an ESP switchboard operator keeping everybody in touch. In between these duties she’s allowed a few costume changes and makeovers, eventually winding up in what appears to be one of Pat Benatar’s outfits.

|

| 1980s style icon Luna |

Meanwhile our hero Joe gets a realistic and satisfying character arc from self-obsessed depressed teen to responsible young adult, only slightly marred by the weird sister complex that probably seemed charming and heartfelt to Japanese audiences, but not to that crowd at the Japan Foundation, palpably cringing at the scene where Joe’s erstwhile girlfriend realizes every other woman in Joe’s life will always play second fiddle to Joe’s sister.

|

| Joe wanders into a Smokey The Bear fire prevention film |

By the time our heroes are levitating above Mt. Fuji, directing scintillating rays of sheer mental force towards the fiery dragon form of beyond-space-and-time evil, somewhere past the two hour mark, that Japan Foundation audience was ready to wrap this up and go home. We’d seen the destruction of Bega’s home planet, we’d watched Luna escape a destroyed 747 and greet the awakened Bega. We’d witnessed Joe move out of self-obsessed sister-complex teenhood, and we’d seen every one of Joe’s friends possessed and/or murdered by Genma’s demons. We’d taken the extended tour of important story beats from five or six Genma Taisen novels and sometimes they fit into the larger narrative and sometimes they just made the hard Japan Foundation seats even harder. Yes there are cushions, but mine was on the floor and I didn’t see it because we showed up late and it was dark, so I guess that one’s my fault.

Not that I didn’t know what I was getting into. My first glimpse of Harmagedon was during the back end of Reagan’s first administration, in the sorely missed Turtles Records & Tapes at Belmont Hills Shopping Center in Smyrna GA - once one of the largest shopping centers in the Southeast, now long demolished. I was a 14 year old prog rock nerd flipping through the ELP section, trying to decide between “Tarkus” or “Brain Salad Surgery,” distracted by a Keith Emerson record with Japanese anime characters on the sleeve, surely a match made in heaven as far as I was concerned. I still have that record.

|

| remember to save your Turtles Saving Stamps! |

Then again, this was the 1980s and Japanese pop culture was infiltrating wherever it could, meaning the bleeping and blooping heard from your local arcade or pizza palace may have been inspired by a Japanese cartoon. This certainly was the case with the 1983 Data East / Nihon Bussan (you may know them as Nichibutsu, the guys who gave us “Crazy Climber” and the strip mah jong video game) laser-disc videogame Bega’s Battle, which used footage and characters from Harmagedon. You may hear “laser-disc videogame” and think of Dragon’s Lair or Cliff Hanger in which gameplay involved joystick movements timed to filmed elements, but Bega’s Battle merely used footage from Harmagedon as background and interstitial elements. Playing Bega’s Battle meant more traditional raster graphics as you controlled Bega in his top-down shooter quest to protect Luna and gather the Psychic Warriors for the ultimate battle with Genma. Did I first see Bega’s Battle in the no-name arcade tucked discreetly behind Turtles in Belmont Hills? Or was it rocking the 2001 arcade in the mall that became the convention center that now hosts our local anime con? Or was it in that weird arcade with the bootleg “Crazy Kong” cabinet, over next to the Japanese grocery store that had the rental VHS tapes, the place where I rented and saw Harmagedon for the first time? Fun fact: a 130 minute film will not fit on an SP-recorded 120 minute tape. But we watched it regardless, clawing meaning from the images in that untranslated Japanese movie, inspired by the glowing colors and the demolished Tokyo and the promise of anime as a cinematic force above and beyond kid-vid TV robots.

Central Park Media would acquire Harmagedon and release it as an English-dubbed VHS and as a dual-language DVD, which is how most 00-era anime fans (and that November Japan Foundation audience) would see it, a seventeen year old archaeological missing link between the 80s overlong SF epic and the more accessible, more action-oriented post-Akira spectacle years. Harmagedon would become a fashionable sneer target for gangs of self-described ‘experts,’ unthinkingly echo-chambering the received “this movie is trash” opinion. And sure, entertainment is a subjective thing, and you can’t expect the 2003 or 2013 cohort to have the same artificially-lengthened attention span we’re cursed with, or to appreciate the shock of the new for something that they didn’t get to see “new” in the first place. But casually dismissing or judging a film out of context, well, that’s foolish. I suggest Harmagedon detractors treat themselves to Haruki Kadokawa’s next animated feature Kenya Boy - you know, the one about the Japanese boy lost in Kenya who is befriended by a benevolent tribesman, becomes a wilderness warrior, rescues the blonde White Jungle Goddess, and defeats the Nazi atomic bomb factory with the help of a giant snake god - and then re-examine their Harmagedon feels.

|

| admittedly, shelling out $39.95 might color my perceptions a bit |

I believe they’ll find, as the Japan Foundation found, that even though the film at times stumbles with clunky updates of very 1960s characters and concepts, perhaps is a little too forceful in delivering its channeling the ascended masters New Religion backstory, and maybe is overlong and indulgent in the very specific way that only a free-spending and possibly substance-addled producer can deliver, even with all this baggage the power of Harmagedon cannot be contained by fire or ice or the ruins of several solar systems worth of civilization, that when this movie works, it works exceedingly well, and that to abandon those moments is to deprive ourselves of everything we watch these cartoons for in the first place. That’s what Genma wants, and we can’t let the Challenge of the Psionics Fighters go unanswered. Can we?

-Dave Merrill

|

| Tao says "fight the power!" |

Thanks for reading Let's Anime! If you enjoyed it and want to show your appreciation for what we do here as part of the Mister Kitty Dot Net world, please consider joining our Patreon!