In the fall of 1979 I was a cartoon-addicted elementary school student, spending my Saturdays with Scooby-Doo and old Warner Brothers shorts on network TV. Weekdays the UHF stations gave us Tom & Jerry, the Super Friends, Speed Racer and Battle Of The Planets. That autumn the elementary school playground gossip was all about a new cartoon that had just started airing on channel 46. This new show was kind of like our favorite film Star Wars, in that it involved outer space battles between zooming fighter-plane starships; but this had something different. Apparently it involved a submarine or a battleship that for some reason was now in outer space. I scoffed. Certainly this was going to be terrible. But the next afternoon I found myself over at a friend’s house and the TV was on and there it was, Star Blazers.

I'd seen other Japanese cartoons before; this one was different. This was a heartfelt, melodramatic space opera whose characters struggled through tears and anger as they travelled one hundred and forty eight thousand light years and back to save everything they cared about, a cartoon that didn't hide its Asian origins as Space Battleship Yamato, but put them right there in the credits. I don't want to underplay the work of Yamato's producer Yoshinobu Nishizaki, but without Leiji Matsumoto we wouldn't have Star Blazers. We wouldn't have those hazy, dark-blue starscapes or the ethereal cosmic goddesses bringing a spark of mystery to the warplanes and battleships of this outer-space World War Two. Without Matsumoto we wouldn't have Yamato, but without Yamato Leiji Matsumoto would still be a titan of the manga world, if just for his melancholy space-train fantasies or his instantly iconic space pirates or his cynical, tragic war comics or his comedies set in hardscrabble down-and-out-in-Tokyo, all drawn with that lush, descriptive brush line, equally at home depicting dinosaurs, cavemen, Type-30 Arisaka rifles, or cosmic super-constructions. Leiji Matsumoto created futures filled with relics and ruins, where myth and legend coexist with science and technology, and where the only constant anyone could rely on was the strength of the human spirit. Sometimes we try to bury history, sometimes we try repeat it, but his world, our world, is everywhere an uncanny, turbulent mix of the past and present, and like Matsumoto's heroes, we can only try to hold fast to our ideals.

Early this year the world lost Leiji Matsumoto. As part of the North American anime fandom that grew around his work, I joined with other fans in presenting various memorial panels at this year's anime festivals. For me it was an opportunity not only to honor his memory and to show off some of my favorite Matsumoto works, but to dig around a little in his back catalog and uncover some things I'd never seen and some facts I might not have known.

I learned he'd been born Akira Matsumoto in Kurume, which is in Fukuoka, down on the island of Kyushu in southern Japan. Even today it's a six hour bullet-train ride from Tokyo. In elementary school his class library had copies of Tezuka's New Treasure Island and Dr. Mars, turning a young Akira into a manga fanatic. He'd be a published manga author while still in school, and when Tezuka was in Kyushu with one of his perpetual looming deadlines, Matsumoto was recruited to be a local assistant.

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw Matsumoto begin a career in shoujo manga, marry fellow manga-ka and sometime collaborator Miyako "Licca-chan" Maki, adopt his pen name Leiji, and move into both science fiction and WWII manga with strips like Burning Southern Cross, Black Zero, Submarine Super 99 and Lightning Ozma, which coincidentally features a space battleship named Yamato.

In mid-1960s issues of Shonen Book, Matsumoto would draw Light Speed Esper, a story about young Hikaru who battles the alien Giron with the super suit created by Professor Asakawa and the help of his adoptive alien parents. Esper is perhaps the most involved SF manga series based on an electronics company mascot, and would also become a pioneering live-action tokusatsu TV show.

Matsumoto's art followed the culture into a more adult-oriented late 1960s as his Sexaroid and Mystery Eve pushed the mature-audiences envelope along with a wider cultural shift towards nudity and adult situations, and his Wheel of Time aesthetic first saw light in Tezuka's COM magazine as the "Fourth Dimensional World" series.

But it was the down-and-out-in-Tokyo loser of Otoko Oidon that gave Matsumoto his first iconic anti-hero, surviving in a four and a half tatami mat room on cheap ramen and home grown mushrooms. The antihero themes would continue in his war comics, beginning with "The Cockpit" and continuing under various names for the rest of his career.

When Nishizaki's Office Academy began preproduction of Space Battleship Yamato, there were several directions open to them. The idea of reviving the Yamato as an outer space warship wasn't a new one, having shown up in pulp fiction, model kits, and even Matsumoto's own Lightning Ozma. But honestly, if you're going to merge WWII and SF then you need to get the guy who's good at both, and that guy is Leiji Matsumoto. Bringing his signature aesthetic to a project that desperately needed a strong visual style, Matsumoto found himself knee-deep in the production of the TV series and its sequels, working on the show and a manga adaptation for Akita Shoten.

His attempt to insert a space pirate into Yamato understandably denied, Matsumoto would make Captain Harlock an important part of 1975's Diver Zero, a story about abandoned Moon androids rebelling against the people of Earth. His mid-70s manga would wander between the high school comedy of Oyashirazu Sanka, the SF of Time Travel Boy Millizer Ban, and in Princess, the feline adventures of Torajima no Mime.

Captain Harlock would get his own manga adventures in Play Comic in 1977. The same year he'd begin Galaxy Express 999 in Shonen King and Wakusei Robo Danguard Ace in Adventure King. This is what the rest of the 1970s would look like, a parade of Leiji-themed TV anime, feature films, radio plays, novelizations, toys, games, and merchandising, seemingly stretching to the Andromeda Galaxy and back. Leiji Matsumoto was busier than ever, yet still found time to take a safari trip to Kenya.

Part of this Matsumotoverse explosion was the premiere of the Westchester Films version of the 1974 and 1978 Space Battleship Yamato TV series. Retitled Star Blazers, this series would air in syndication across America where it would convince not only myself but an entire generation that Japanese animation was an exciting and innovative medium, and we needed to fill our lives with as much of it as humanly possible.

The "Yamato boom", fed by Matsumoto's visual style, would fade away as the 1980s anime world switched gears towards idol singers, transforming robots, and obnoxious aliens. SSX and the Queen Millennia anime series would both have truncated seasons, the Yamato herself would have its final voyage in 1983, but Matsumoto's manga kept right on, continuing his Battlefield series with Hard Metal in Big Comic and giving Japan a third Black Ship Crisis in Fuji Evening Paper.

Never one to abandon icons, Matsumoto would throw Harlock and his crew into Wagner's Ring Of The Nibelungen in, of all places, the pages of "Used Car Fanatic," while his Battlefield series continued with "Case Hard" and the mysteries of Leonardo Da Vinci's genius were explored in "The Angel's Space-Time Ship."

The mid 1990s meant Yamato-boom kids were now adults, inspired by Matsumoto to work in his style and produce new animated versions of his works. One of the best of these later-period adaptations is the three-part OVA series The Cockpit, delivering three punchy antiwar stories from his Battlefield series.

A new Galaxy Express film and a home video adaptation of his Queen Emeraldas manga arrived in 1998, while Matsumoto produced the historical epic manga Shadow Warrior. Captain Harlock's Wagner cycle would make the anime transition in 1999, Cosmo Warrior Zero would fly through the same universe in 2001, and Harlock would revert to the "Herlock" spelling for a Rin Taro-directed video series in 2002.

An entire new generation of eyeballs would see Leiji Matsumoto's style as French electronic music robots Daft Punk built an entire album around a Matsumotoverse theme with their 2003 album/film Interstella 5555. At both Anime North and AWA I met audience members for whom 5555 was their first exposure to Leiji Matsumoto's work.

The oughts would see a parade of new Matsumoto anime that included versions of Gun Frontier and Submarine Super 99, the lengthy Galaxy Express side series Galaxy Railways, and an abortive attempt to rework Space Battleship Yamato into Dai Yamato Zero-go, which found its greatest success in the medium of Pachislot. In 2006 Matsumoto would bring his manga career full circle with Firefly Yokai, a new take on his first published manga, 1954's Honey-Bee Adventures.

Prepping for these panels, I conferred with several friends in Japan who'd met Matsumoto and were familiar with his studio, and I gathered some interesting facts from their experiences. For instance, Patrick Ijima-Washburn told me that he'd asked Matsumoto about his favorite comic from the West. Matsumoto thought he was talking about Westerns, meaning cowboy movies, and replied that his favorite Western was the 1954 Joan Crawford film "Johnny Guitar."

Dan Kanemitsu, The Man from I.O.E.A. (the International Otaku Expo Association) related to me how former Matsumoto assistant, Yattaran inspiration and Area 88 artist Kaoru Shintani was working with fellow Studio Leiji-sha employees one day when a taxi pulled up and Matsumoto hustled in with a big mysterious bundle he'd just spent all his cash on, a bundle that turned out to be an actual Revi C 12/D gunsight from a Messerschmitt, you know, the star of several Matsumoto Battlefield manga stories, a key element in the film Arcadia Of My Youth, and an object Leiji had just spent every bit of ready cash on, could someone please pay the taxi?

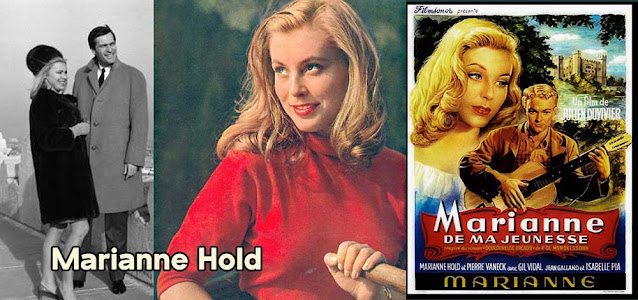

Speaking of youths and Arcadias, anime journalist Darius Washington made sure I knew that Matsumoto's model for his mysterious, aristocratic blonde characters was the German Heimatfilm actress Marianne Hold, the star of dozens of films including 1955's "Marianne Of My Youth."

I also spent a little time assembling an online mixtape of music from various Leiji Matsumoto projects, which you can listen to over at Mister Kitty dot Net.

As for myself, my interest in Star Blazers led me to join one of the American anime clubs that grew out of the show's success on American TV, and soon I found myself running an anime club in my home town, writing fanfic, drawing fan art, publishing anime zines, attending one of the first anime conventions, and writing professionally about Japanese animation for a variety of print and online media. Eventually I'd help start our own anime convention, still going strong 28 years later, and along the way I'd make thousands of friends. Without that anime fandom, without Leiji Matsumoto, I and many like me would have had a very different path.

“(Leiji) Matsumoto used to say, ‘At the faraway point where the rings of time come together, we shall meet again,’” Studio Leiji-sha director Makiko Matsumoto said in their statement. Leiji Matsumoto was the author of thousands of pages of manga, countless adaptations, characters, and adventures, recognized with the Japanese Medal of Honor With Purple Ribbon and the Order Of The Rising Sun as well as the Knight Of The Order Of Arts And Letters from France, and on February 13, 2023, he succumbed to acute heart failure in a Tokyo hospital.

Eulogizing Tochiro Oyama's passing in the film Galaxy Express 999, Tetsuro Hoshino says "being human means you also have to face death... whether you've fulfilled your dreams or not." Leiji Matsumoto's dreams were right there in the pages of his manga, dreams of romance, struggle, honor, violence, eroticism, humor, and the human spirit's ability to transcend time and space itself. He may be gone, but those dreams will remain with us, always.

-Dave Merrill

thanks to Patrick Ijima-Washburn, Dan Kanemitsu, Darius Washington, and L. Matsumoto.