In

September I presented this piece at Anime Weekend Atlanta. Thirty years back

(!!), I was part of Atlanta

Thirty years ago Japanese anime

fandom in the United

States

They were the latest in a series of anime fan surges that had

been washing over North America repeatedly since the early 1960s, each fed in

turn by syndication of Astro Boy, Kimba, Gigantor, Marine Boy, Prince Planet,

Tobor The Eighth Man, and Speed Racer, sometimes Princess Knight or a UHF television

broadcast of Jack And the Witch. All this foreign TV input coalesced into

fandom in the late 70s, when Japanese-language UHF began broadcasting superrobots and when home video technology reached the point where such broadcasts

could be replayed over and over again to audiences of fans. These “Japanimation” fans would gather in LA, SF and NYC to

watch poorly subtitled TV cartoons and 16mm prints of Astro Boy episodes; and

they’d form the first Japanese animation fan group, the Cartoon/Fantasy

Organization (C/FO).

Sandy Frank’s iteration of Tatsunoko’s Gatchaman, Battle Of The

Planets, began syndication in September of 1978. BOTP fans would shortly start

the second national anime group to come to any sort of prominence, the Battle

Of The Planets Fan Club. Organized in early 1979 by Ohio ’s

Joey Buchanan, the BOTP FC would be active through the mid 1980s, with outreach

via classified ads in Starlog.

|

| BOTP Fan Club newsletters (thanks to G.) |

Star Blazers, the American version of Space Battleship Yamato,

would air in September of 1979; it inspired still more fans, clubs,

newsletters, and even the first Star Blazers-themed anime conventions. For

those hooked at home or converted via anime screenings at local comic &

Star Trek shows, the BOTP, the Star Blazers

club and the C/FO became the next stop for learning more about “Japanimation.”

Our Class Of ’85 spent 1984 taping episodes of Voltron from

local TV, wishing for Star Blazers re-runs, waiting to hear back from that

anime club they contacted after they found their flyer at the local comic con, and

finally taking matters into their own hands. They’d find a few fellow fans with

enough Japanese animation on videotape to reasonably entertain an audience for

five or six hours and were crazy enough to volunteer to do all the work of

hauling televisions and VCRs and boxes of tapes, and somebody would find a

space they could meet once a month. Repeat in cities across the US

and Canada :

anime club.

|

| C/FO Magazine, the national club's publication |

When Robotech - Harmony Gold’s localization of Tatsunoko’s

Macross, Southern Cross and Mospeada - made its syndicated TV debut in the fall

of 1985, “Japanimation” fandom was already in place and ready for its close-up,

Mr DeMille. Newly minted anime fans

would learn of the Macross feature film, they’d find out that their favorite

arcade game “Cliff Hanger” was assembled from a couple of Lupin III

feature films, that there was an entire slew of Japanese cartoons about alien

high school students and vampire hunters and mercenary fighter pilots and

teenage trouble consultants and ESP

policemen, that there was already two and a half decades of Japanese animation

to get caught up on and more happening all the time.

(I’m using “class of 85” here as glib shorthand for the whole

1984-1987 time frame. 1985 was when our local anime fans got together but

meetings didn’t get regular until ‘86. 1987 was our busiest year and the winter

of 1988-89 was when our club, like many other C/FO affiliated clubs, fractured

beyond repair. Anyway my high school yearbook with Julia Roberts’ photo is from

1985, so “Class Of 1985” it becomes. )

|

| now showing at your local anime club meeting |

Get comfortable. Anime club meetings lasted for hours, with a

mix of films, TV episodes, and OVAs showing on the main television for as long

as possible. Titles screened would typically be in Japanese without benefit of

subtitles, though there was a thriving market in photocopied English synopsis

guides describing who was doing what to whom. Occasionally a more fluent (or delusional)

member would appoint himself facilitator and provide running commentary, which

would degenerate into a crowd of people attempting to top each other’s humorous

pre-MST3K commentary. Members would socialize in the back of the room or in the

hall, play RPG games, draw fan artwork, sell each other anime merchandise

they’d picked up and didn’t want, build model kits, and generally display

future anime-con behavior.

It was a golden age for home video retailers. The dust was

still settling from the Format Wars and Sony’s Beta was sinking fast, mortally

wounded by VHS in the marketplaces of North America .

Early VCR adopters paid $1000-$1500 for the

privilege, but 1985 consumers saw top of the line machines retailing for less

than $600, with bargain models at around $150 - prices anime fans could afford

even on their part-time after-school K-mart salary. The technology itself had progressed

from top-loading, wired remote, mono decks to 4-head stereo machines capable of

crystal-clear freeze frame images, all the better to view bootlegged Japanese

cartoons with.

|

| Print advertising for VCRs circa 1985 |

Maximizing our AV experience was a must, and this might involve

splitting the RF signal to two or more TVs, giving the whole crowd a decent

shot at enjoying Fight! Iczer One. Thrift-store receivers and speakers would delight

and/or annoy the patrons with a rough approximation of stereo sound. The Class

Of ’85 learned that no anime club meeting was complete without a daisy chain of

VCRs wired together in the back of the room, distributing that newly acquired

tape of Vampire Hunter D down the whirring line of VHS decks with the end of

the chain getting the worst of the deal.

Where did those tapes come from? A thriving Japanese home video

market put direct-to video anime releases, feature anime films and the

occasional TV collection on the shelves of Tsutaya video rental outlets.

Japanese fandom, just beginning to call itself “otaku”, was taping anime

off-air, as seen in the fine documentary film “1985 Graffiti Of Otaku Generation”, later exchanging copies of these tapes with US

pen pals. Servicemen stationed in Japan

spent their garrison pay on blank videotape while fans in American cities with

Japanese minorities were learning to haunt the local Japanese neighborhoods in

search of video rental stores.

|

| your choice: kidvid or homebrew |

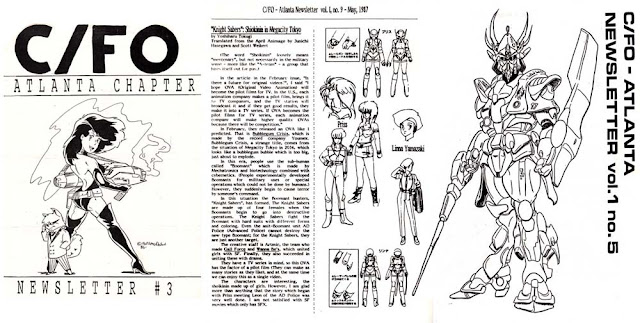

Promoting their new anime clubs was also a struggle. Using the

internet for wide promotion and informational purposes was still in its

infancy; anime clubs had to get the word out using old-fashioned print. Just as

cheap home video technology enabled videotape-based TV fandom, cheap photocopy

technology was causing a fanzine explosion, and fans would take full advantage

of Kinko’s and related outlets. Xeroxed

flyers would promote the club in comic book stores and at fan conventions.

Members would be informed of upcoming meetings via a monthly newsletter

assembled out of whatever fan art could be harvested and whatever anime news

could be gleaned from magazines, the news media, and the wishful thinking of

fellow fans. Assembling these newsletters meant an extra day or so of work

every month for the club officers, all published without benefit of scanners or

graphic design software, just typewriters, white-out, scissors, and glue.

Copied, collated, stapled, addressed and stamped, the final product would then

be subject to the mercies of the United States Post Office.

|

| getting the word out about Bubblegum Crisis |

1985’s anime fans would also suffer the burdens of

international economic policy. The Plaza Accords meant a rising yen vs the US

dollar. This, and natural supply and demand dynamics, inflated the US

prices of anime goods. In Japan ,

the anime market shrank from the “anime boom” years of 1982-84 even as their

“Bubble Economy” swelled preparatory to bursting.

Happily ignorant of the larger economic forces, the Class Of

‘85’s local clubs kept meeting at its libraries and community centers,

publishing its newsletters, screening anime at comic cons and Fantasy Fairs to

appreciative crowds and grumbling con organizers, swapping tapes and making

road trips and generally living the 80s anime fan lifestyle of pizza,

Coca-Cola, and late nights spent copying Project A-Ko over and over. What they

lacked in data or tech they made up for in brotherhood; a typical anime club

meeting might include a potluck junk-food smorgasbord, a surprise birthday celebration

or a post-meeting dinner, with fans from three or four states turning anime

club meetings into impromptu anime family reunions.

|

| the Atlanta club in its natural environment |

As a chapter of a national organization, the local club had

certain obligations to the parent body. In practice these obligations were

vaguely defined and generally involved swapping newsletters, tapes and gossip

with other chapters. At one point the national C/FO was sending a Yawata-Uma

horse (a gaily painted hand carved wooden horse given as a gift on special

occasions) from chapter to chapter to be decorated with signatures and mascot

illustrations; this arrived, was duly scrawled upon, and delivered to the next

link in the chain, perhaps the pinnacle of cooperative achievement for any

national anime club. Photos of this horse eventually wound up in the March 1987

issue of Animage, along with pictures of American cosplayers and members of Atlanta ’s

local club.

|

| Yawata-Uma & fans captured on home video in somebody's basement |

What finally happened to the Class of ’85 after the ‘80s ended?

The Battle Of The Planets club had long since vanished, while the national Star

Blazers club leveraged its reach and became Project A-Kon. The national

leadership of the C/FO used parliamentary procedure to reduce what had been 30+

chapters in three nations to a few local Southern California

clubs. Former C/FO chapters became sovereign anime-club states charting their

own anime club destinies, while other clubs that never bothered with the C/FO

kept right on doing what they’d been doing all along. For example; the Anime

Hasshin club, by virtue of a lively and regularly-published newsletter, a

tape-trading group, and a total lack of interest in hosting meetings or

chapters, became a leader in the 90s anime fan community.

|

| join a local anime club today |

1990 saw the start of the direct-to-video, uncut, English

subtitled localization industry with AnimEigo’s Madox-01. Films like Akira

would put Japanese animation into the art-house cinema circuit and finally,

into the cultural lexicon as something other than Speed Racer. Local anime

clubs began their long slide into irrelevance, faced with Blockbuster’s anime

shelves and Genie or Compuserve’s dedicated anime boards. University anime

groups, with giant lecture halls, professional video presentation equipment,

and a captive audience of bored nerds, sprang up wholly independently of any extant

fan networks. The anime club officers of the 1980s were growing up, graduating

college, getting married, moving on to careers and lives beyond a monthly

appointment to deliver Japanese cartoons to a roomful of fans, some of whom

hadn’t bathed or been to the Laundromat in a while.

They’re still around, that Class Of ’85. You can probably find

a few survivors at your local anime con holding forth behind a panel table or

on a couch in the hotel lobby, spinning tales of what fandom was like in the

days of laser discs and Beta tapes. Some are no longer with us, living on in

photographs, the dot matrix print of club newsletters, and in the fond memories

of their fellow anime fans. Others have

moved on to the far corners of the Earth or across town, in a world that now

recognizes the truth of what they were trying to say three decades ago. Turns

out this Japanese animation thing is pretty cool after all.

|

| so long, Bill. |

Thanks for reading Let's Anime! If you enjoyed it and want to show your appreciation for what we do here as part of the Mister Kitty Dot Net world, please consider joining our Patreon!

1 comment:

I totally love this kind of posts of yours. Bring back a lot of memories: things were similar even in other countries. Great read, mate.

Post a Comment