On September 9, 1999, at 9:09am (Japan Standard Time), disaster will strike the Earth! Speeding by on its thousand-year orbit, the giant planet Lar Metal will miss us by inches, but in its wake comes destruction on a vast scale. Professor Amamori of the Tsukuba Observatory struggles with the biggest astronomical news of the century, along with his orphaned nephew Hajime and Amamori’s assistant Yukino Yayoi, a mysterious beauty burdened with an awesome secret and a terrible decision that will affect the destiny of both planets.

This is the story of Queen Millennia (Japanese title 新竹取物語 1000年女王 or Shin Taketori Monogatari: Sennen Joō, or "The New Tale of the Bamboo Cutter: Millennium Queen,") Leiji Matsumoto’s followup to his popular Galaxy Express 999. Queen Millennia would appear as a manga series, a TV show, a radio drama, and a 1982 feature film, released just as the TV anime was reaching its climax. A blizzard of Queen Millennia ballyhoo buried print and broadcast media in a blanket of thousand-year hype, leading some wags to describe the property as "The Queen Of Promotions."

The North American anime fandom of the Club Era (1977-1995) knew of Queen Millennia thanks to Roman Albums, anime magazines, and the occasional 5th generation VHS copy. Unlike some other anime of the period, the Millennia film was mercifully spared an edited, weirdly-dubbed American release, and even the fan subtitle crowd hadn’t caught up with it. So it was up to our Atlanta-based Corn Pone Flicks fansub group to get the job done. We had our pal Sue's script and our pal Shaun's LaserDisc, and soon it was one more star in the CPF fan subtitle galaxy.

|

| script and final product |

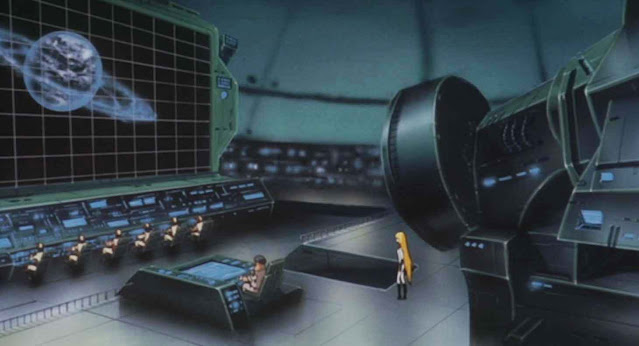

Expecting rock-em sock-em SF adventure from that Queen Millennia fansub? This film delivers its struggles on a more spiritual scale, opening with a closeup of Yayoi’s long-lashed brown eyes slowly receding into space, advising everyone to get comfortable and settle in. Queen Millennia spends a lot of its run time showing us slow-moving planets, leisurely floating continents, and Lar Metal’s space invasion armada gently manoeuvring into formation, all set to a Kitarō soundtrack that inspires restful contemplation rather than cinematic excitement.

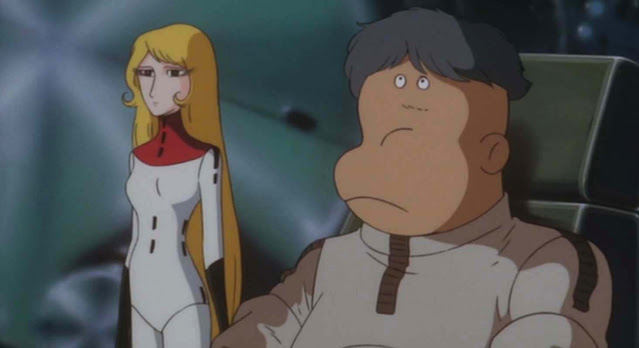

The movie covers the major plot points of the Queen Millennia mythos; Junior high schooler Hajime suffers the sudden loss of his parents and an uncomfortable new life with astronomer Uncle Amamori, while crushing hard on his math teacher Yayoi and worrying about, you know, that whole impending When Worlds Collide thing. Hajime escapes a meteor-smashed Tokyo to a hollow-Earth survival shelter and learns not only was his engineer father somehow involved with the Lar Metal, but that his dream gal is actually cosmic royalty in the final days of her thousand year term secretly ruling mankind. Yayoi, a space-age Princess Kaguya (there’s that “Tale Of The Bamboo Cutter” tagline) now doing business as Queen Millennia, finds herself forced to reconcile sister Selene’s rebellion with the Earth emigration plan of her Lar Metalian fiancée Dr. Fara, while at the same time dealing with the anti-Earthling prejudice and unwanted affections of her Captain Harlock lookalike subordinate Daisuke Yamori. Ultimately, Yayoi must choose between her home planet and the Earth she’s purportedly been in charge of. And I say “purportedly” because judging by the last thousand years it doesn’t look like anybody’s been in charge.

|

| Yayoi in regulation astronomy leotard |

It’s an occupational hazard of adapted media, but sometimes watching the cinematic Queen Millennia is an exercise in spotting things the TV show and the manga did better. Yayoi spends much of her TV time dressed down in denim, chilling with her adopted parents and her all-purpose Leiji Matsumoto cat in their mom & pop ramen shop, letting us know she honestly enjoys the low-fi Earthling lifestyle. TV’s Amamori gets to spend more time hectoring the military-industrial complex and their takeover of his observatory (Macek’s script for the Harmony Gold version literally names it “The Military Industrial Complex” in his version, a Boomer child’s callback to Eisenhower if ever there was one). Hajime is allowed time to grieve lost parents and mix with schoolyard friends and rivals to mix. Selene leans into her resistance fighter persona and gives the viewer a fun masked mystery character.

The movie version abandons all this in favor of long, lingering shots of planets, spaceships, floating chunks of Japan, and Lar Metal’s airbrushed Roger Dean album cover landscape. On the other hand, the film ditches the manga scene where Yayoi goes to Venus in an Lar Metal insectoid spaceship controlled by her entire, jaybird-naked body, Iczer One style, and that’s probably OK.

|

| Leiji Matsumoto self-insert fanfic |

The film’s distinct visual style is almost a character in its own right. We think of the 80s as being neon grids, primary colors, and high-tech hairstyles, but every decade has echoes of its past and countercultures always flourish in the margins. The occult had spent the 1940s and 50s strictly for cult religions and professional Nightmare Alley spook-show grifters, but these and other alternative worldviews gained new energy from the upheaval of the 1960s, as disaffected youth sought meaning and purpose away from stupid, vulgar, greedy ugly American death-suckers. This hunger for alternative spiritual meaning became known as the New Age Movement in the 1970s, embracing everything from Tibetan shamanism, Ayahuasca-fueled mystery ceremonies, the Rev. Moon, the Hare Krishna, spirit channeling, UFO contactees from countless planets, and the untapped powers of an entire flea market full of crystals, rainbows, dream catchers, pewter angels, gazing balls, and incense. The entire patchouli-scented parade was still marching sandal-clad strong into and throughout the 1980s.

Queen Millennia is wall to wall carpeted with these baroque, rainbow-crystal-healing-vibration hallmarks of the New Age, where there's a seeker born every minute. We’d see this junk science permeate pulp fiction of the time and Leiji’s was no exception; for instance, the Erich von Däniken ancient astronaut underpinnings of his Space Pirate Captain Harlock. Interviewed before Queen Millennia’s release, Matsumoto went so far as to describe the film as “occult-like.”

Earth ruled by powerful hidden adepts? This is old-school Hollow Earth Shaver Mystery stuff crossed with Madame Blavatsky’s Ascended Masters trip. Unseen Tenth Planets causing Earthly cataclysm and disaster is the backbone of numerous mid-century kook-science theories, the granddaddy of which is Worlds In Collision by Immanuel Velikovsky, a NYT best seller (!!) that suggests the planet Venus erupted from Jupiter four thousand years ago, and whose wild orbital journey caused most of the miracles of the Old Testament before it settled down in its current position. The scene in Queen Millennia where Lar Metal approaches Earth and we see a giant spark as the electric potential of the two planets equalizes? Straight outta Velikovsky. As a wild wild planet bonus, the film even gives us its version of Von Daniken wannabe Zecharia Sitchin’s "dark star" Nibiru, the rogue planet that killed the dinosaurs and has us next on its hit list. Don’t trust those Zeta Reticuli brain implants, kids.

|

| Queen Millennia Book Club reading list |

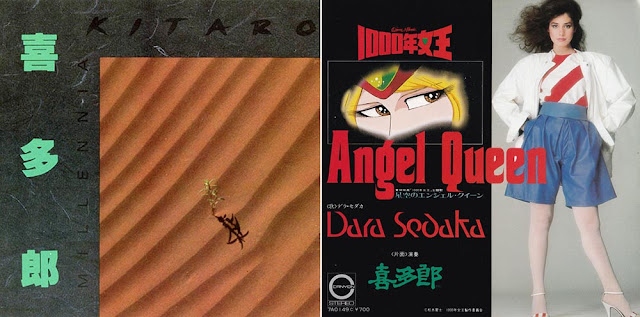

Kitarō or Masanori Takahashi is, of course, the renowned Japanese electronic-instrumental composer, blending folk, classical, and electronic music into what millions of late-night public radio listeners know as New Age music. Coming into prominence with his score for the 1980 NHK documentary "The Silk Road," his albums first saw wide American release when he signed with Geffen, who packaged six earlier and one new LP for the US market. American anime nerds, their pop culture radar antennae already alert for any Asian content, were quick to spot Kitarō's records. As with Harmagedon, this gave us the opportunity to purchase the soundtrack for a film we couldn't yet see.

|

| Queen Millennia Record Club selections |

Putting Kitarō on the Millennia soundtrack assignment is a strong signal that this movie isn't going to be a typical Matsumotoverse space-warship pass in review; the composer's new-age reputation amplifies the film's new age themes. Of course, even harmonic convergences aren’t immune to the power of pop music, and as a counterpoint to Kitaro's spacey harmonics, American singer Dara Sedaka, daughter of Neil "Believe In The Sign Of Zeta" Sedaka, delivers Queen Millennia’s end-title tune "Angel Queen" (Canyon – 7A0149c).

All these new-agey cultural highlights might make for fascinating cultural analysis, maybe, but they aren’t enough to elevate Queen Millennia, a film that dazedly unspools its slow-paced story with animation that plods and rarely soars. The big secret of who Yayoi is and what she’s up to is unwrapped in the first ten minutes, leaving the viewer to glean what excitement they can from duelling space fleets and potato-head Matsumoto characters firing giant prop crossbows at alien fighters, only to be confused and bemused when the retired Millennial Queens rise from their Millennial Tombs and transform themselves into space ships, Turbo Teen style. By the film’s end we’re watching an entire rogue galaxy rushing towards us at Einstein-defying speeds, a deus ex machina climax that feels less like universal destiny and more like last-minute writer’s room panic.

|

| Voice talent, creatives, and Kitaro at Queen Millennia event |

Queen Millennia shares a lot of staff with a different Toei SF epic, 1980’s Cyborg 009 Legend Of The Super Galaxy. Character designer/animation director Yasuhiro Yamaguchi, literal cult director Masayuki Akehi, mechanical designer Koichi Tsunoda, and DP Tamio Hosoda worked on both films, each featuring impractical yet stylish spacecraft, scripts and running times that freely bend the laws of time and space, and blatant references to the debunked theories of human history being influenced by ancient astronautics. Queen Millennia screenwriter Keisuke Fujiwara has written for literally hundreds of films and TV episodes, including 55 episodes of GE 999 and 53 episodes of Mazinger Z, making him perhaps the hardest working writer in anime-show business.

The film has seen French, Spanish, Chinese and Italian releases, but so far North American licensors have yet to give Queen Millennia any sort of home video outing. I’ve no doubt the questionable performance of the mid 80s Harmony Gold series influenced decisions at some point, and the film’s then-groundbreaking production committee financing might make for complicated licensing rights. Acquiring rights to the Kitarō soundtrack can’t help but add an extra layer of licensing-lawyer billable hours to the whole mess. Even today in North America’s anime-saturated market here aren’t a lot of companies willing to go that extra Millennia mile, and this is a shame. Queen Millennia is like no other film inspired by Leiji Matsumoto works; it is first and foremost a tragedy, the desires and wishes and struggles of ordinary and even supernaturally advanced peoples meaningless against the immense, unstoppable power of the cosmos itself. Will fans of early 80s SF anime and fans of new age synthesizer soundscapes ever be able to come together in front of the TV and enjoy a film made just for them? Or will one of those rogue planets or out of control galaxies stumble out of outer space and smash us to bits first? I’d say odds are about even. See you in the underground caverns!

-Dave Merrill

Thanks for reading Let's Anime! If you enjoyed it and want to show your appreciation for what we do here as part of the Mister Kitty Dot Net world, please consider joining our Patreon!!

1 comment:

Dear Dave,

Thank you for (yet another) great article. You have a very good point about how the past echoes into the present--and somehow the New Age movement, a well-known phenomenon at the time (the Harmonic Convergence happened, or didn't happen, a few weeks after my first trip to Japan) often gets left out of depictions of the 1980s. The mention of Kitaro’s Queen Millennia soundtrack reminded me of how I used to specifically seek out its presence when I was in a record store, as if it was a secret sign left there only for anime fans--it wasn't, of course; it was there because it was Kitaro, but somehow seeing any reference to anime within a mainstream American venue around 1982 or '83 gave a thrill. That may not seem like much of a thrill, but of course, crack didn't arrive until the OAV era.

A friend of mine in college--the only one of us college station DJs who actually went on to work in radio professionally--had a mix-tape library he carried in a briefcase that contained every Billboard #1 hit from the 1950s to the present day, in chronological order. Listening to it was what made me realize for the first time how memories of an era get filtered and edited (or, if you're bucking for a M.A., mediated). For example, the 1966 tape had both "Sunshine Superman" and "The Ballad of the Green Berets" on it, but only the former song would be on the playlist of an oldies station today. And yet, it turned out "Sunshine Superman" spent only one week at #1, whereas "The Ballad of the Green Berets" spent five weeks there--longer than any other song in 1966 (a year when its competition included the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Beach Boys--not to mention Frank Sinatra and Petula Clark). Now, Donovan's song may be more fun to listen to, but to leave out the way SSgt Barry Sadler ruled the charts, it seems to me, also leaves out something of the full social reality of 1966 in the US.

—C.

Post a Comment